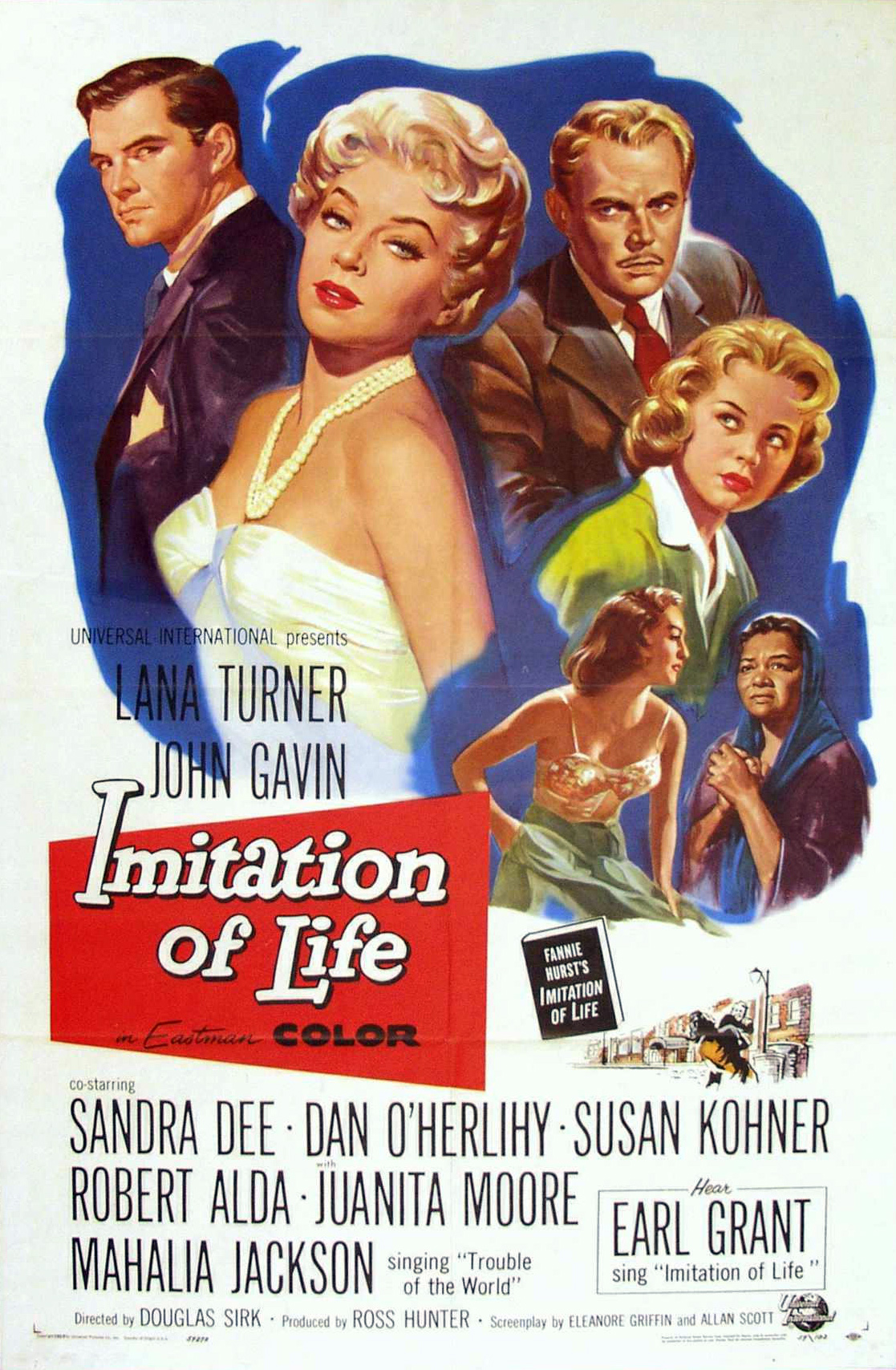

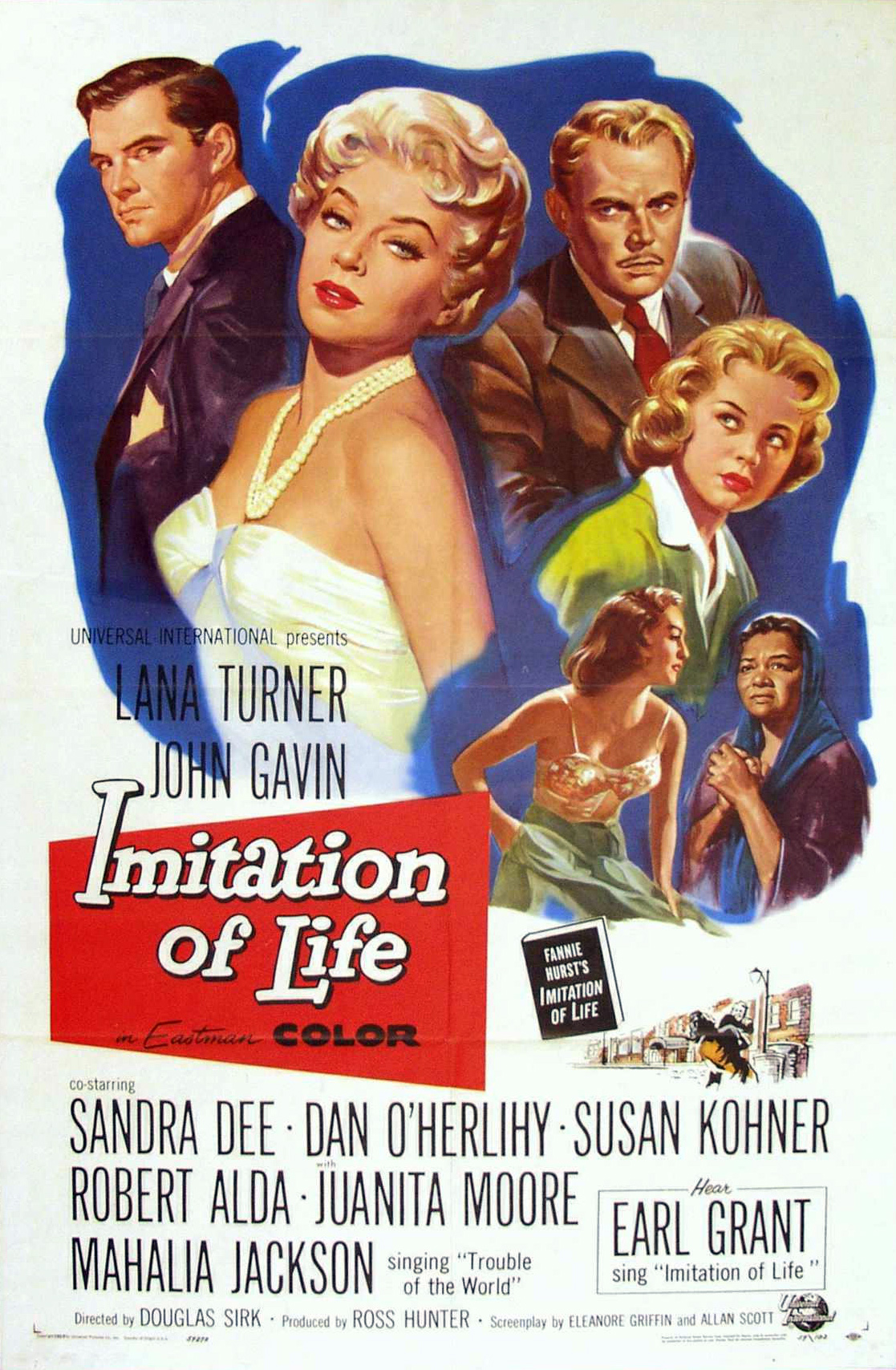

Filmmaking is constantly evolving; style, genre, and even, interpretation go through particular periods in which their already established significance is reshaped. Melodramas, with a superficial viewing, can be perceived as merely movies with informing musical cues; the theatrical substance associated with an ever-growing 1950’s bourgeoisie. However, The interpretation of Douglas Sirk’s melodramas; All That Heaven Allows (1955), Written on the Wind (1956), and Imitation of Life (1959) through the auteuristic manipulation of the foreground, background, and overall mise-en-scene, can reveal formulated social commentaries regarding complacent politics of race, gender, and sexuality.

The 1950’s was a period in history where men and women worked within their distinct social responsibilities. Moving out of the World War II era; a brief moment in time where the lines between genders roles were seemingly blurred, society successfully transitioned into a period of containment. Barbara Klinger describes the 1950’s cultural landscape as, “a time of …apparent complacency.” (8) Images commonly associated with the 1950’s, such as a woman cooking over a hot oven, her fedora-wearing husband trekking into the office, and their eventual dinner-table reunion, showcase a clear display of consensual complacency, as well as the automaton-like nature society was embracing. Additionally, this newly found complacency within the bourgeois regarded gender, sexuality, and race through specific binaries that found each to be established as black or white. In other words, there was no changing the social patterns that were perceived as normal and acceptable.

Douglas Sirk’s melodramas, working through the 1950’s cultural landscape, have been recently reconsidered as works of a skillful auteur. Regarding the relationship between things, Sirk considered that “Objects in the mise-en-scene…embody [a] social critique.” (Klinger 9). Much like an author carefully constructs meaning within a novel through the minute details, actions, or dialogue, Sirk is working through a similar sensibility, one that utilizes the mise-en-scene to represent decodable ideas revolving around social commentary. For example in, All That Heaven Allows, Sirk, by utilizing the mise-en-scene, surrounds the characters with distant trophies, ornaments, and statues to evoke a presentable richness but at the same time, an internal emptiness. This can specifically be noticed moments before Cary and Harvey leave on their date. Sirks decision to include such objects, though simplistic, can only warrant conversation, one that considers interpretable meaning and its plausible relationship to a larger social emptiness. In this case, Sirk is allowing his eloquent mise-en-scene to articulate ideas regarding complacent attitudes of the 1950’s bourgeoisie. In many ways Sirk’s mastery over the mise-en-scene alludes to upcoming narratives and thematics of his films; All That Heaven Allows, being no exception.

Sirks auteuristic methods must also concern his ability to create, arguably the most important aspect of a melodrama, the aesthetic. All That Heaven Allows, Written on the Wind, and Imitation of Life, all work through similar apparatuses. As stated by Bordwell and Thompson, the melodrama is presented by “Psychologically impotent men and gallantly suffering women [who] play out their dramas in expressionistic pools of color…” (314). Sirk’s melodramas are not attempting to recreate the subtleties of natural life; a responsibility that neorealism filmmakers cultivated. Instead, Sirk’s melodramas are hyper-realistic representations of the 1950’s bourgeoisie reality. Moreover, Sirk’s melodramatic aesthetic utilizes a wide variety of embellished musical cues and emotional highs that reveal, to the audience, significant plot point developments. This can explicitly be observed in Written on the Wind when Lucy, cloaked in dark blue expressionistic lighting, finds a gun under Kyle’s pillow, or when Marylee walks in on Mitch strumming the ukulele. The lighting, clearly unrealistic, helps to build the visual aesthetic melodrama needs, as a genre, function.

By understanding Sirk’s auteurism, as well as the social landscape of the 1950’s, maneuvering through the politics of melodrama becomes much more accessible. All That Heaven Allows follows a relationship between Carey and Ron. The new-found romance is the talk of the town, simply due to the fact that Cary is an older woman and Ron is much younger. The film is obsessed with objects; objects that are idealized, like televisions, the objects within the mise-en-scene, as well as, the object of social norms. As stated before, objects fill the room, yet they appear to serve a superficial function, a reminder of mindlessness, boredom, and even artificial company. It is even suggested that to cope with her husband’s death, Cary should invest in a T.V., to, as is stated in the film, “Keep busy”. Interestingly enough, Sirk seems to juxtapose the artificiality with shots of blooming trees, almost as if he is trying to compare the differences between the two. The comparison seems to comment on the 1950’s artificiality; the patterns of living, objects of affection, and reasoning for affection. Sirk brilliantly takes this critique and parallels a similar theme alongside Ron, Carey, and the gossiping town. While romance between a young man and older woman would be considered taboo, through the norms of 1955, they decided to break away from the artifice of society and follow what feels natural.

Written on the Wind also appears to be assessing particular artificial aspects of the 1950’s social foundation. Following the customary traditions of the melodrama genre, Written on the Wind presents a mentally impotent man, Kyle, who is constantly being surpassed by his friend and business ally, Mitch. The two male protagonists fall in love with Lucy and, like most films, drama inevitably runs its course. Sirk, throughout the movie, is keen on exploring the expected roles of men and women; so much so, that the evaluation leads Kyle to his death. Due to the gendered politics of 1956, Written on the Wind dares to explore the “familial social definitions of masculinity.” (Klinger 23). Kyle is victimized by his history of being, in many ways, less of a man than Mitch; inlying the matter of being castrated in a patriarchal social order. Examined in the bar fight, Kyle, an alcoholic, is seemingly defeated by some random drunkard. By being punched on to a table, Kyle ultimately becomes part of the background and, inherently, part of the mise-en-scene. Shortly after this happens, Mitch, after landing a knockout punch, defeats the same drunkard. It appears Sirk does not want Kyle to regain any sense of his male dominance, but rather suggests a different way of thinking and seeing. This new point of view employed by Sirk, “Protest against the realist convention and the ideology it upholds.”(Klinger 24); meaning that Written on the Wind, by being a melodrama, is commenting and critiquing the problematic understanding of masculinity. By framing masculinity through the melodramas over-stylized, hyper-realistic, and emotionally high aesthetic, a viewer gets to witness a gendered illogicality of the 1950’s social order.

Feminism is also a topic Sirk explores, specifically, through the dance sequence. Starting with a high angle shot that pushes into the estate’s window, the camera appears as an all-seeing eye. Initially, the camera, still in its authoritative position, presents an extraordinarily gendered conversation about football; ultimately concluding with one of the women stating, “I’ll never know who’s got the ball.” As the words fade, Marylee, clearly unaccompanied, moves into the frame. Sirk, with just one shot, has made a profound statement in relationship to womanhood. The authoritative, nearly judge-like, angle of the camera allows for a viewer to consider the perceived normality of female behavior and, in many ways, psychology. Next is a medium shot of Marylee, in the background, entering into a dark room; she is shrouded in darkness as if her intentions are untrustworthy or maybe unclear. Shortly after, Sirk presents a series of shots, all of which consist of Marylee dancing. The suggestive dancing acts as an outlet for Marylee to express her sexual frustration regarding Mitch and the rest of society. The standout sequence, “beautifully exemplifies the sexual thematics of the film: frustration and impotence.” (Klinger 25). By placing sexual themes through Marylee, it appears the Sirk is, once again, breaking away from the dominant ideology of the 1950’s.

Shifting to Imitation of Life, another film that communicates via mise-en-scene, camera movement, and critiques on racial identities, one can notice, again Sirks auteurism. Positioned in the background of the mise-en-scene, a majority of the film is an African American maid, Annie, who is struggling to maintain a relationship with her race-denying daughter. Meanwhile, at the forefront, Lora Meredith, an aspiring actress, attempts to create a life of luxury by participating in various Broadway plays and movies. Even with just a basic understanding of the plot, it becomes apparent that the more socially conscious narrative of the film would be centered on Annie and her struggle with racial identities. Despite the fact that Annie is often seen associating with a plethora of maids and butlers; all of which find a defined spot in the opulent-looking background of the film, it is her story that, through Sirk’s auteurism, cannot help but find a place of chief importance.

Shifting to Imitation of Life, another film that communicates via mise-en-scene, camera movement, and critiques on racial identities, one can notice, again Sirks auteurism. Positioned in the background of the mise-en-scene, a majority of the film is an African American maid, Annie, who is struggling to maintain a relationship with her race-denying daughter. Meanwhile, at the forefront, Lora Meredith, an aspiring actress, attempts to create a life of luxury by participating in various Broadway plays and movies. Even with just a basic understanding of the plot, it becomes apparent that the more socially conscious narrative of the film would be centered on Annie and her struggle with racial identities. Despite the fact that Annie is often seen associating with a plethora of maids and butlers; all of which find a defined spot in the opulent-looking background of the film, it is her story that, through Sirk’s auteurism, cannot help but find a place of chief importance.

Imitation of Life’s racial conversation, visually, alludes to the types of identity, equality, and binary obstacles that plagued the 1950’s. In other words, Sirks directing was visually capturing “current” cultural inequalities and at the same time, maneuvering through their complexities via the genre of melodrama. When Sara-Jane meets Frankie near the end of the film she is once again confronted by 1950’s racial discrimination. A medium shot, stating the sequence, shows Sarah-Jane as she anxiously awaits her boyfriend. Frankie, a shadowy figure in the background, quickly approaches. Sara-Jane rushes over to Frankie and, together, they both stand in the distant expressionistic shadows. Sirks decision to have the medium shot grow into a long shot is, perhaps, alluding to the fact that there is a recently discovered cultural distance between the two characters (Frankie being white and Sarah-Jane being black). The next shot is a medium close-up of Sarah-Jane and Frankie; however, after a quick pan left, Sarah-Jane is reflected through a window of a bar. The mirrored image of Sara-Jane seems to evoke an idea concerning the unstable image; something that becomes exceedingly apparent when one recalls her own identity struggles. As Frankie, just seconds later, exclaims, “is your mother a nigger?” Sirk pans right and reintroduces Sarah-Jane into the shot. By utilizing this pan, Sirk forces an immediate, in your face confrontation of the 1950’s racial binaural reality. As the sequence continues, Sarah Jane, through another reflected shot, begins to get assaulted by Frankie. The refection of Frankie slapping Sarah Jane is a powerful image on its own; however, its significance is only elevated when considering that Sirk seems to be suggesting ideas about the instability within identity, as well as the flipped reality of what Sarah Jane ultimately desired.

Sirks ability to critique the 1950’s social climate and at the same time, confront it with auteurism, can be attributed to the mise-en-scene. Klinger describes, “mise-en-scene as a site that generates commentary…” (22). Using the previously detailed sequence; Sirk’s lighting, alleyway-setting, and mirror-usage, all work in unison to present an evaluation of what lies, “beneath the surface” (Klinger 22). Imitation of Life, through Sirk’s direction, appears to be merely an imitation of 1950’s complacency (Lora Meredith’s narrative) and at the same time, an imitation of the period’s racial struggle (Annie/Sarah Jane’s narrative) that can be thoroughly explored and assets via the mise-en-scene.

The ending of Sirk’s melodramas are considered, “false happy-endings” (Klinger 23); concluding with the death of a character who has experienced some sort of superficial and interpretable turmoil. In the case of Imitation of Life, Sarah-Jane rushing to her mother’s funeral showcases a narrative conclusion but in many ways, also articulates the cost of racism through mise-en-scene. While it could be understood that Sarah-Jane, as she mourns over her mother’s casket, has finally realized the importance of her mother, the non-happy ending would permit that underneath the superficiality of the bouquets and mourners, Sara-Jane has finally accepted her societal circumstance. She is African American and has felt first-hand; the ramifications of racism are unavoidable. In many ways, the ending of Imation of Life is not wrapped up with a tightly knotted bow-tie. The reality is that there could be another story to tell; the lives of every character, by the end of the film, seem to be in a place of indecisive ambiguity. By not letting anyone fulfill the desire to know what happens next, Sirk suggests that these issues are currently haunting the 1950’s social agenda.

All That Heaven Allows, Written on the Wind, and Imitation of Life are capturing specific attitudes of the 1950’s and casting them through Hollywood lenses, auteuristic sensibilities, and masterful mise-en-scene. Social critiques, commentaries, and concerns, are presented to audiences through the melodramatic aesthetic and at the same time hidden through that very system. Often the landscape of society influences art and it appears that Sirk’s films are heavily influenced by the politics of identity. It also appears that not many other films were attempting to work through these types of differing logics. Sirk stands out as a director who constantly let the societal views take shape within his films.

Douglas Sirk was able to take the genre of melodrama and turn it into a field of political/ social conversation. By utilizing the endless possibilities of mise-en-scene, camera movement, and character arcs, Sirk presented the 1950’s audience with, at times, subtle critiques of what was lying beneath the surface of a complacent major reality. His films took on a particular self-aware style that allowed for such cultural explorations to feel as though they were, indeed, true explorations of ideologies. All That Heaven Allows, Written on the Wind, and Imitation of Life are all films that appear as ordinary melodramas full of clichéd emotions and plot points; however, upon a closer look, the films are seemingly packed with mise-en-scene that fuel interpretable meanings. The films, mise-en-scenes, and meanings all attempted to bring a new conversation to the world of the 1950’s.

– Reddmond Perone

Works Cited

Boredwell and Thompson. Film History: An Introduction. 3rd ed., Mcgraw-Hill 2010

Klinger, Barbara. Melodrama and Meaning: History, Culture, and the Films of Douglas Sirk. Indiana University Press, 1994.

Shifting to Imitation of Life, another film that communicates via mise-en-scene, camera movement, and critiques on racial identities, one can notice, again Sirks auteurism. Positioned in the background of the mise-en-scene, a majority of the film is an African American maid, Annie, who is struggling to maintain a relationship with her race-denying daughter. Meanwhile, at the forefront, Lora Meredith, an aspiring actress, attempts to create a life of luxury by participating in various Broadway plays and movies. Even with just a basic understanding of the plot, it becomes apparent that the more socially conscious narrative of the film would be centered on Annie and her struggle with racial identities. Despite the fact that Annie is often seen associating with a plethora of maids and butlers; all of which find a defined spot in the opulent-looking background of the film, it is her story that, through Sirk’s auteurism, cannot help but find a place of chief importance.

Shifting to Imitation of Life, another film that communicates via mise-en-scene, camera movement, and critiques on racial identities, one can notice, again Sirks auteurism. Positioned in the background of the mise-en-scene, a majority of the film is an African American maid, Annie, who is struggling to maintain a relationship with her race-denying daughter. Meanwhile, at the forefront, Lora Meredith, an aspiring actress, attempts to create a life of luxury by participating in various Broadway plays and movies. Even with just a basic understanding of the plot, it becomes apparent that the more socially conscious narrative of the film would be centered on Annie and her struggle with racial identities. Despite the fact that Annie is often seen associating with a plethora of maids and butlers; all of which find a defined spot in the opulent-looking background of the film, it is her story that, through Sirk’s auteurism, cannot help but find a place of chief importance.